| The Sandisfield Times |

|---|

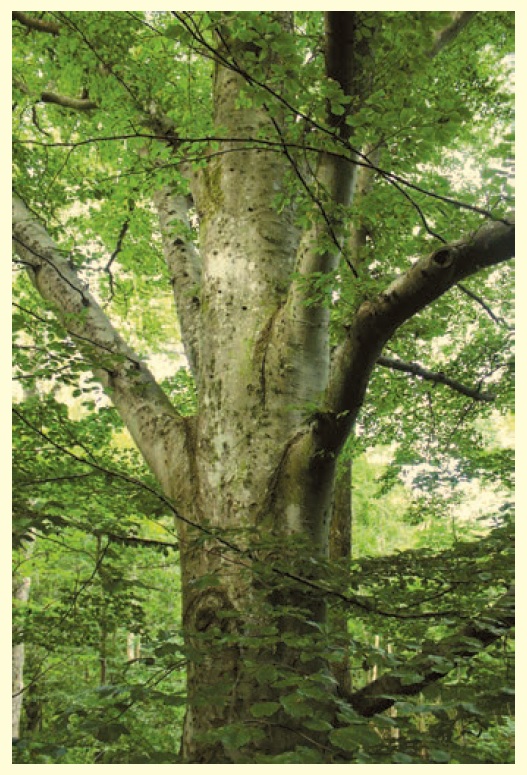

| Are Our Forests Dying?

Not Dying as Much as Changing |

|

by Tom Christopher Published September 1, 2025 |

|

If you've stepped into the Sandisfield woods recently, you have noticed that another of its foundational tree species is struggling. The leaves on our native American beeches (Fagus grandifolia) emerged this spring striped with dark bands, and as the season progressed they have curled, grown leathery, and in many cases fallen from the trees. These are all symptoms of a new parasite, a microscopic round worm or "nematode" that feeds inside the buds before they open. The resulting damage reduces the trees' ability to photosynthesize and use sunlight to power the production of food. In the case of small specimens, the infestation commonly leads to the trees' death within a year or two; larger, mature trees may hang on longer, struggling on for as much as a decade before dying. Like most of our recent tree epidemics, this one seems to have been introduced from abroad. The nematode, Litylenchus crenatae mccannii, was first observed in Japan, where it is just a minor pest as it does not seriously affect the health of Japanese species of beeches. How it traveled to North America is unknown, but it seems likely to have hitchhiked in Japanese beech trees imported for sale to gardeners. |

|

|

This is a common cause of our tree epidemics. North America was actually part of the same landmass as Asia until 200 million years ago. Because of this, Asian and American forests are populated with related trees. After the two continents drifted apart, the two forest floras evolved along different lines, as did the local pests that preyed on each. The much larger forests of Asia developed all sorts of parasites and diseases - because these co-evolved with the local trees, over millennia the trees there developed a natural resistance to infection. North American trees, because they had no contact with the Asian pests, did not evolve a similar resistance. When Asian pests and pathogens from Asia are abruptly introduced into America in a shipment of nursery stock, they find trees related to their Asian hosts but with no defenses. What had been a modest pest in the Asian homeland becomes a mass killer here. The most recent U.S. Forest Service census indicates that just under 10% of the trees with a trunk diameter of 1 inch or more in the Massachusetts woods are beeches. The disappearance of so many trees will have a huge impact on our forest ecology. The loss of the American beech will deprive trees over 100 species of native butterflies and moths, as well as many other native insects, of an important food source. The caterpillars, in particular, are an important food source for the chicks of many native songbirds. The nuts born by American beeches are a high protein and fat food source for many mammals and birds, including red, gray and flying squirrels, chipmunks, bears, blue jays, tufted titmice, wild turkeys, and ruffed and spruce Grouse. As serious as the loss of this tree species may be, it is just one element of an ongoing transformation of the Northeastern forest. Many other exotic tree species imported by gardeners have also served as transportation for other devastating Eurasian pests and diseases. Chestnut blight, a hitchhiker on imported Asian chestnut trees, stripped our woodlands of American chestnuts, one of the most common hardwoods, in the early 20th century, and dogwood anthracnose, an imported fungal disease, has reduced wild populations of our native flowering dogwood by 90% in some areas.

Other pest introductions have been a by-product of international trade. The emerald ash borer, an Asian insect that has largely extirpated our native ash trees, is believed to have arrived in wooden packing materials from Asia. Dutch Elm disease, a fungal disease that despite its name seems to have originated in Asia and eastern Europe, arrived with imported lumber. Meanwhile, our warming climate has allowed cold-sensitive tree pests to colonize areas such as ours where winter cold once excluded them. Last year, for example, I noticed that the hemlock trees around my Sandisfield home had become infested with hemlock woolly adelgid, an insect parasite that has already eliminated that tree species from most of its southern range. According to Dr. Dorothy Peteet of Columbia University, changes in forest composition have been a periodic feature at least since the end of the last ice age 11,500 years ago. Dr. Peteet is a palynologist, a type of scientist who studies pollen grains which have been preserved in bogs and lakebed sediments, sometimes for hundreds of thousands of years. Each species of flowering plant produces a distinctive shape of pollen grain. By identifying and then carbon dating the pollen found at different levels in the sediments, palinologists can reconstruct the flora of the surrounding area at different epochs. This provides insights into the local climate of that period as well as changes in the character of the vegetative cover. Dr. Peteet noted that the palynological record reveals that hemlock trees disappeared temporarily from the Northeast 5,000 to 7,000 years ago, most likely because severe and extended droughts reduced the trees' resistance to native insect pests. Likewise, during the Younger Dryas, a 1,200-year cold spell that set in circa 12,800 years ago, existing forest trees in the northeast were temporarily replaced by species from more northern regions. However, she added, the current abrupt disappearance of tree species here, with its consequent impacts on loss of wildlife numbers and diversity, are unprecedented, at least since the last episode of mass extinctions 66 million years ago when the impact of a massive asteroid ended the career of the dinosaurs and the loss of an estimated 75% of plant and animal species worldwide. The current disappearance of so many tree species from the Sandisfield woods has the inevitable effect of opening up countless gaps in the forest canopy, which creates an opportunity for other trees and shrubs to move in. Many of these new arrivals are likely to be aggressive invasive foreign trees and shrubs (the majority of which were also introduced into our landscape by gardeners). This disturbance of the flora is being reinforced by climate change, which is already eliminating such iconic trees such as the sugar maple from the central New England landscape. As I've noted, gardeners have played a significant role in contributing to the destabilization of our forests. We can also make a positive contribution. When we seek new trees for our yards, we should look to native species that flourish in the states to our south, which flourish in the higher temperatures we are experiencing. Unlike the invasive new arrivals, these natives do help support North American wildlife and so are a superior alternative. To expedite this sort of plant transfer from south to north, the northeast division of RISCC (the Regional Invasive Species and Climate Change Network) has created a free online guide. Founded to connect scientists with land managers and planners and promote innovative and more effective strategies to counter these two threats, RISCC's northeast division is based at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This past summer, it published "Climate-Smart Gardening 2.0: Plants to Promote Climate Adaptation." Available for download at scholarworks.umass.edu, this document is the fruits of an exhaustive search of 339 major nurseries in the Northeast and MidAtlantic regions for plants, including flowers, grasses, shrubs, and trees, that are native to the eastern United States and which, judging by a number of criteria, should flourish in the northeastern states as the average temperatures rise. Many of the plants are labeled as "near-natives;" that is, they are not indigenous to our region now but currently native to nearby states and are predicted to fare well in the climate Massachusetts will experience by the middle of this century. The lists of recommended plants, which are grouped by states, also includes information of interest to gardeners such as each species' preferences for level of sunlight as soil type, the color and season of its bloom, as well as services it provides to pollinators and other wildlife. This will be my most useful tool for replacing the ashes and beech trees I am having to remove from my Sandisfield yard. After all, if I plant a tree, I want it to endure for decades. Likewise, I want it to nourish the birds, bears, and butterflies that I call neighbors. |

©The Sandisfield Times. All rights reserved.

Published September 1, 2025